How Green Activists Destroyed America's Most Intense Beauty, Lothlórien, the Valley of Singing Gold

Backing them, the richest families on earth

It is as if giant psychotic five-year-olds had moved into their county, ripped out its industry, pulled up the train tracks, broke the weirs and dams, introduced predators to kill cattle and horses, and methodically ruined family after family, ranch after ranch, forest after forest. And then left, delighted at their “progress,” never to return.

It rained all night last night which means this morning the sun is not occluded by the forest fires which rage now every summer, blocking the sun, leaving us breathing smoke. The next three pieces are a deep dive on why this is happening. It is an easy fix, return to the 150 years of German silvaculture that managed forests all over the world. Forestry is an exact science. It knows when and how to burn, when to thin, and importantly how to manage. All over the world, courtesy of the cursed U.N., forests are not-managed deliberately. And so they burn and burn and burn.

Why are people all over the world so angry? Because the regime described below is being forced everywhere and it is destroying people, economy and land. Why is the economy in such a treacherous dangerous position? Why do we teeter at the edge of collapse? This. It started right here. Let the lady sheep-farmer describe just how surreptitiously screwed we have been. All of us. Everywhere.

It’s Not About the Spotted Owl

I am standing on the flatbed of a three-quarter-ton pickup with Kathy McKay of the K Diamond K Ranch in Republic, Washington, hanging on to a bale of straw as the truck rocks its way down a steep incline into a vast field. It is snowing and the snow is already two feet deep. As we lurch and grind, about a hundred horses spot us, turn, and as if animated by a single puppet master, start to run toward us. They are backlit by snow-covered trees ranked up the snow-covered mountain.

For the next ninety minutes, we peel six-inch layers of hay off the bales and kick them in pieces into a gaggle of horses, then jerk on to the next stomping, nickering group. A slip on the mud and slush and I’d be under the feet of six or seven dancing hungry horses. But the exhilaration is inexpressible, and not for the first time I envy the people who live out here, who live like this, working outside every day no matter the weather, using their muscles and sinew for a purpose other than “health” or longevity. There is a sense here that there is no place else. For me, Ferry County, Washington, has a kind of limerence—I’ve known about its drama for years, and seeing its beauty, I understand the dedication of those who are so beaten, so thoroughly thrashed, outmatched, and ruined. It is as if giant psychotic five-year-olds had moved into their county, ripped out its industry, pulled up the train tracks, broke the weirs and dams, introduced predators to kill cattle and horses, and methodically ruined family after family, ranch after ranch, forest after forest. And then left, delighted at their “progress,” never to return.

“We’re dying here,” says Republic Mayor Shirley Couse, whose life has been lived so hard, she looks twenty years older than she is. She has a cold today, so she sniffles through our meeting. She is a volunteer mayor. At first she stepped into the post when someone fell sick, and since then no one has run against her. There’s nothing fun about managing decline. She ticks off her problems, then adds, “The only thing that’s saving us is the gold mine that was recently reopened.

And even with it, we are a welfare county.”

Ferry County is the poorest rural county in the state and is the U.S. county most affected by the actions of environmental activists. Once rich, with a high median income, now desperate, still it shimmers with gold, and an occasional fantasist like me can see the glitter underneath the snow and trees, the narrow valleys, the wide flat rivers and strip malls, junkyards, and gas stations. Gold founded Ferry County, and surveyors claim the region holds all twenty-nine minerals named in the Bible. Ferry and its neighbors—Stevens, Colville, Okanagan, all the counties in the Columbia basin—together form a lost fairyland of dense forest, white-capped mountains, narrow valleys, rivers, creeks, and wetlands—like Lothlórien, the Land of the Valley of Singing Gold from The Lord of the Rings.

The action that started the ruination of Ferry County is the most stunning success of the modern environmental movement, the northern spotted-owl campaign in the 1990s, which shut down 90 percent of the productive forests of the American West. It required only a few months of marching, political pressure, direct actions (sometimes called ecoterrorism), and a typical Clintonesque deal, which drew off some of the Left’s fire for his ratification of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), but embedded in that campaign lies the corruption at the heart of the modern movement. Andy Stahl, then resource analyst with the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund, declared: “Thank goodness the spotted owl evolved in the Northwest, for if it hadn’t, we’d have to genetically engineer it. It’s the perfect species for use as a surrogate.”

And a surrogate it was. The reason the bird was so convenient was that it ranged over an extraordinarily large home area, each breeding pair apparently depending on thousands of acres of old-growth forest. Eric Forsman, the doctoral candidate in biology whose three studies were the only studies cited during the listing hearings on the bird, admits to this day that knowledge of the bird is limited at best. According to forest policy analyst Jim Peterson, despite sixteen years of research, no link between old-growth harvesting and declining owl populations has ever been established. Those few logging companies still operational from California to Alaska are required to provide owl habitat and actively manage their lands. They report the highest reproductive rates ever recorded for spotted owls. Two years after the ban, more than eleven thousand northern spotted owls were counted, many of them nesting in second-growth forests and clear-cuts. But the Fish and Wildlife Service would not delist the species. It was fruitless to claim, as many disinterested biologists did, that the northern spotted owl’s decline was due to its being preyed upon by the larger barred owl, which had begun moving west a hundred years ago. Or that federal scientists flatly rejected critiques from biometricians who questioned the statistical validity of evidence on which the listing decision was based. The movement got what it wanted. The largest, most productive, fastest-growing temperate rain forest in the world had been shuttered.

“Culture is far more fragile than nature,” said Alston Chase as we said good-bye.

Indeed, the culture of the Washington, Oregon, and Montana forests was pitched almost immediately into trauma. According to timber consultant Paul Ehinger in Oregon, 430 sawmills have closed in the West since 1988, when the war of the woods began. The job losses in the milling and logging industries exceed fifty thousand. And for every forestry job lost, up to five jobs are lost in the businesses and industries that serve the forestry sector. Two hundred fifty thousand family-wage jobs is a mighty blow, and the impacts just keep rolling. Today in Eureka, Montana, there are half as many school-age children entering the system as leaving it. Says County Commissioner Marian Roose: “We have a new eight-million-dollar school and we have no idea how we’ll pay for it now. Who is going to contribute to our local charities? Who is going to contribute to Little League? Who is going to buy the children’s stock at our annual fair 4-H sale? I bet it won’t be the attorney for the Ecology Center.” For the past decade, the only businesses making money in Ferry County are the U-Haul franchise and storage lockers.

In the nearby Kootenai National Forest, whose 2.5 million acres grow almost 500 million new board feet every year, 300 million board feet die due to windthrow, insects, and disease. Salvaging and selling that wood could have fed the families of the counties surrounding that forest. “If we don’t remove some of this fuel,” says Bruce Vincent, a third-generation logger, “we are simply stacking 300-million board feet of firewood in our forest, in our watersheds, around our communities, and around our homes.”

In fact, says Holly Fretwell, the shutdown of the forests, the banning of both thinning and the removal of dead trees, even burned trees, has set up a once-in-a-millennium event. More than 700 million acres of once productive federal and private lands have been set aside under stringent land-use restrictions by federal mandate—three times the size of Texas, or 30 percent of the entire nation. Fretwell says that Forest Service experts are convinced that 90 to 200 million of those acres are at risk of cataclysmic fire.

The death of wildlife and endangered species in those fires will far outweigh lives lost to industrialization. Fretwell reports that Theodore Kaczynski, a freshwater biologist working on salmon recovery strategies, says, “No single forest practice—not timber harvesting, nor road building—can compare with the damage wildfires are inflicting on fish and fish habitat.” Not to mention the dead birds, elk, deer, bears, voles and salamanders, trees, and other vegetation, as well as lower summer water volume and increased erosion. The forest can be regenerated. The fish may never return.

Banning thinning has caused 80 percent of the trees in the forests of the Pacific Northwest to become infested with root rot and beetles. The elk and the antelope are gone in many of the forests; the deadfall is too high to climb and the forests too choked to browse. The large predators, wolves and bears, reintroduced at the insistence of the movement, are driven by the twenty-foot-high deadfall barriers in the upper forest ranges to forage close to inhabited areas. The resulting loss of sheep and cows can be a blow to a family now merely subsisting. In some rural communities in Montana, school bus stops look like cages, and investigations are now confirming wolf kills of humans. The behavior of introduced wolves is changing, and not in a good way. And if the movement, despairing of pure wolf stock in North America is indeed bringing in Russian cadaver wolves with average weight 250 pounds and a taste for human flesh, who among us is going to leave a paved road in the backcountry?

“I wish,” says outgoing county commissioner Joe Bond, “that when these people showed up thirty years ago asking where there was a nice place to eat, we’d pointed them three hundred miles west to Seattle. I say that as a joke, because I enjoy the people who came. But some of those people moved in here and said we don’t need the mill anymore. That was when we were running three shifts a day at Boggins Mill and people had good jobs, the kind of jobs that can support a family.”

Joe Bond was head saw filer at Boggins Mill for twenty-nine years until Clinton shuttered the Western forest on behalf of the spotted owl. “One guy loses his job, but he has a wife and three kids, so five people move out of the county. Each good forestry job creates between three and five service- or industry-related jobs, so that means if 150 of us foresters lose their jobs, that means 600 jobs lost. If 600 family-wage jobs are lost then, you lose 3,000 people. One time our school had 600 kids; now it’s 325 kids. Our hospital is in trouble, because the older people who move here to retire, when they go to a doctor, they go to Spokane, so it’s just the younger families who use it. Even people my age have left.”

Bond’s voice is low and gravelly, and I’m not sure—it’s late at night, the snow is deep on the ground, getting around was hard today, and we are all tired—but at times I think he is trying to suppress tears. His house is comfortable and well appointed; it gleams through the dark. His wife, Nicole, who runs a beauty salon out of the house, sits with us. They keep a few horses, pets now, since their children had to move to find work. “We watched them take the mill apart,” he continues. “It was heartbreaking for our community. After the mill went away, the railroad was bought by a company that bought it for two million and scrapped it out for four million, and rail-banked it with the county. From cutting a hundred million board feet a year, we went to one million.”

“What happened to the forest?”

There is a long pause. “It’s dying.”

He clears his throat. “The forests are warehoused. It’s dying, overstocked. Have you been over Sherman Pass? It’s that thirty-mile-an-hour corner on the way to Colville. The hillsides up there are turning brown. Where the fire was in ’88—that was just a big waste. They wouldn’t let the sawmill take the timber, not even three or four years later. A big log-home company from Montana came over, and they wouldn’t even let them have the logs for log homes. I talked to a lot of old-timers, and they think that if they had been allowed to go in there with saws and cut a lot of that back down, they would have driven the seeds into the ground and it would have come back a whole lot faster.

“Now we have overgrowth and root rot. I know Okanogan County has moth in their timber; they were trying to spray it, but activists launched a suit to stop it. We know what will happen. The forests in northern BC are gone. At one time, we were buying that beetle-kill timber. Now there’s no timber coming down from Canada.”

His wife chips in. “They want it to be wilderness.”

“How likely is that here?” I ask. Wilderness designations are widely feared in working country.

Big, big sigh from Joe. “They keep at it all the time—there was a big turnover in DC, and wilderness is designated by Congress. It didn’t get designated right now, so they have a lot of other fish to fry there.”

“Tell her about the dams and what they’re doing about that.”

“These are small dams on cricks. They’re removing them for the purpose of man never ever leaving his footprint on the national forest, easier for them to have their wilderness. Under the 1964 Wilderness Act, it says “unimpeded by man.” If you’re going to treat something as wilderness and there’s a crick out there with an eight-foot-wide dam, well it doesn’t qualify as a wilderness. So they’re ripping them out. Everything dies then. It goes to desertification and the water just vanishes.

“They promised that tourism and retirees would make up the difference. As county commissioner, I see all the stats. There’s no economic benefit from retirees. Most people who retire here stay seven years and leave. They hit seventy-two or -three, they have to drive to Spokane to see a specialist, they put their houses on the market and leave. There’s no tourism. A hundred and fifty people lost their jobs from the mill alone. Those were family-wage jobs that had medical insurance. To create an equivalent 150 jobs in tourism, you’d have to build a Disneyland.”

I drive up to Sharon Shumate’s house outside of Republic, Washington, walk in a wide circle around the giant Great Pyrenees wolf-and-bear-killing dog, who is far too stern to submit to my wiles, and settle at the linoleum table. I spend at least half the interview marveling at this woman in her seventies, a sheep farmer, living in an ancient bungalow with a peeling floor and a kitchen so thoroughly unrenovated that I feel shot back in time.

I wake up from my trance when I realize that not only that she is schooling me in the history of the movement, but that she is doing it in a manner so clear, so stripped of commentary or emotion, that it is the most succinct I’ve either heard or read.

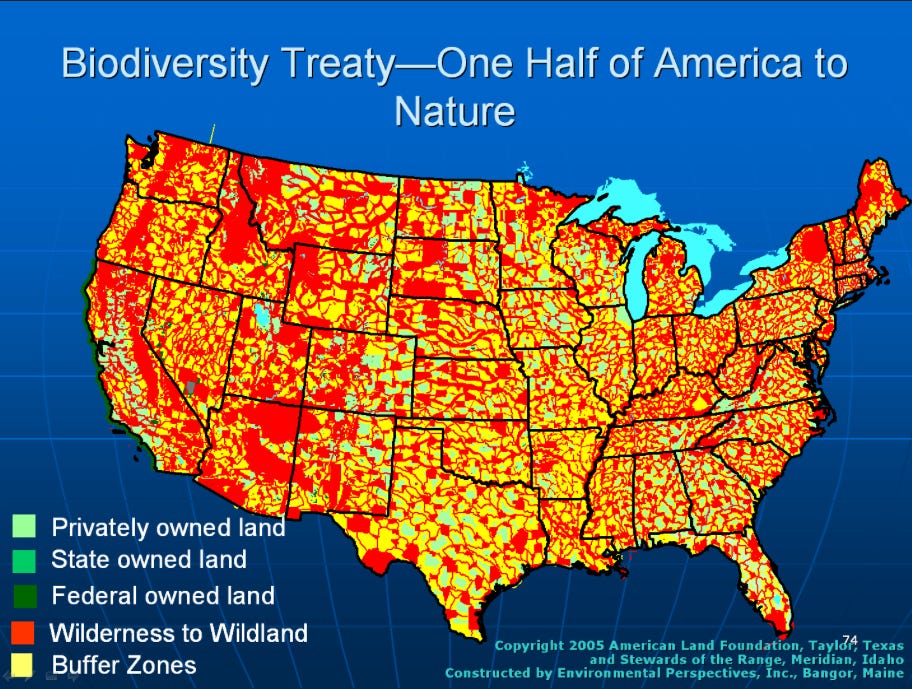

“Have you seen the map of what they want?” I nod distractedly, as she presents it.This map, called the Wildlands Project map, was developed from a close reading of the documents detailing the UN’s Convention on Biological Diversity, and it rocketed through rural America like a dose of salts.

“That’s what they want,” she snaps. Sharon has prepared files for me—homework, as it were—detailing the history of the fight in Ferry County. “We fall first because we’re the poorest. If we fall, they can take out the rest easily, and not just the rest of Washington State. They’ll take out every rural county. They test strategy and tactics here. What they’ve done is launch multiple attacks on every level, hoping to overwhelm us. It all comes from the IUCN, [International Union for the Conservation of Nature] that’s where we’ve sourced many of their plans.”

“Like what?” It seems as if I’m always dragging people off the precipice of paranoia.

“ Their priority habitat and species list, for example. They want us to list twenty-nine ‘species of interest’ here, and our planning commission refused. Some of those species have never existed here, according to their own research. But they think that the species would thrive here, so they want to introduce them—like, for instance, the Oregon spotted frog. Why? And where did this list come from? Fish and Wildlife does not claim to have written it; the Department of Ecology does not claim it. It didn’t come from the ESA. [Endangered Species Act] bureaucracy either. We finally found it at the IUCN. Just like the biodiversity map. Even if they didn’t get that treaty ratified in Congress in 1988, they’re implementing it piecemeal.

“So after the Biodiversity Treaty failed, they instituted ICBEMP [pronounced ICE-bump. “That’s when I got involved, because in 1992, I was head of the Sheep Farmers Association. We defeated ICBEMP, but they put in place the Washington State Growth Management plan right away.”

“How do they manage growth if there is no growth?” I ask.

She looks at me with beady eyes for a moment, then throws back her head and laughs. “It’s growth for them; they get paid to plan! They submit these templates as models, and that’s what gets written as ordinances. They don’t acknowledge their linkages and associations.

“The Growth Management Act required each county to develop a comprehensive plan to develop regulations for their critical areas. There are five critical areas defined: aquifer, aquifer recharge areas, geologically unstable areas, floodplains, and fish and wildlife protection areas. These last are the source of greatest conflict.

“At its inception, the Growth Management Act was fairly broad-brush, not overtly threatening to everybody. They offered grants and funding to counties who were doing planning under the act, and they encouraged each county to have a planning department in their county government—provided grants for those county planners; it was how they got into it. Since then, each session of the legislature manages to add a little more to it, broaden the requirements and more teeth to go along with it.

“Now we have forty-eight separate documents for management and conservation programs, status reports, recovery plans, and wildlife research, for which Ferry County residents are supposed to supply habitat designation and document best available science. Further, nine state agencies are in perpetual motion, buying land to conserve.”

Sharon attended agricultural college, then moved to Ferry County in 1988 to ranch sheep. At the time, there were sheep-grazing allotments in the Colville National Forest. But almost as soon as she got set up, the Forest Service began pulling existing leases and refusing new ones.

“It was then we started having our forest fires. Sheep and cattle grazing together keep down all the noxious weeds and brush; they do a fantastic job. Now graze has to be kept four inches high, or animals have to be taken off. Junk science, we call it.”

When Sharon Shumate says “junk science,” she is referring to the results, because the results are junk. Washington state calls it best available science, or BAS. There are a half dozen best-available-management strategies, all of which come from the Codex Alimentarius, out of the World Health Organization and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Codex Alimentarius claims to set international standards for “good safe food”; what it does is overturn generations of local rural knowledge, its eventual aim, claim rural people, to police all food production and force it to conform to international standards.

“So-called best available science tends to be kind of consensus science—some people at an agency, say Fish and Wildlife, come up with a theory, think it’s maybe kinda true, and promote that as their science,” says Sharon. “Take the battle we have been fighting for years now: one or two hundred feet buffer width on streams. They want to keep water temperatures at a certain level; they want shade for the water; they want plant life on east side of the shores; and they want large woody debris to be able to fall into the creeks. Those conditions are promoted as ‘best available science.’

“It means essentially, ‘Let’s see what everyone else is doing and we’ll put together a synthesis and publish that as best available science.’ Commerce doesn’t distinguish; it treats that document as the absolute gospel truth, despite the fact that the authors say right in it that it’s not meant to apply specifically. After Commerce has put its imprimatur on the “science,” the rest of the agencies treat it as the scriptures of God. If they get it put through here, then they can tout it as being in use in other places.”

Ferry County has thrown up some of the most effective fighters for rural people in the county. In 2000, Lenape Indian Diana White Horse Capp published a book called Brother against Brother: America’s New War over Land Rights. In it, Capp—who testified before Congress in 2000 and received multiple death threats for her efforts—says that environmental activists stirred up the tribe on the Colville reservation and paid them to support the movement’s objectives in Ferry County. Indians on the Colville reservation have intermarried with whites for more than a hundred years, which meant families were being torn apart.

Ten years on, three legislators fight every step of the way. Shelly Short in Washington state is advancing a bill that would require that each piece of science-based regulation affecting rural Washington state receives independent peer review. Defeated in April 2011, it will almost certainly pass in the next session, the first such legislation in North America. Representative Joel Kretz forced the legislature in Washington to reject the Yellowstone-to-Yukon wildlife corridor. In D.C., Cathy McMorris Rodgers fights the good fight against a tidal wave of money and lobbyists.

I visit Kretz and his wife, Sarah, in their house in Ferry County. It is a typical rancher’s house—timber frame, worn, comfortable, with a three-mile driveway. Kretz and his wife breed mustangs, do a little timber harvesting, and run a score of mother cows.

“Yeah, I remember Mitch Freedman from Earth First throwing horse shit down the ventilators at the mills. I got involved a few years ago, when we were doing short loads, logging with horses, just light thinning, stand-improvement stuff. Our culverts were working fine. Then some guy from the Department of Natural Resources comes up and says ‘as part of your privilege of being able to harvest your timber, we want you to put in a twelve-thousand-dollar arc-style bottomless culvert to save salmon.’

“Now, four things have to happen before I save salmon in Bodie Creek. They gotta jump the Grand Coulee Dam, they gotta jump the Chief Joe Dam, they have to jump the sixty-foot waterfall on the Kettle River, and then they have to cross a quarter-mile of rocky ground to get to this culvert so I can save it. Plus, it’s a seasonal runoff ditch; it only holds water for six weeks a year.

“So,” he continues, “after we called them on that, it became bull trout, which they introduced into the creeks and called native and endangered. All of us on the creek got letters saying you have thirty days to comply or daily fines will be levied. So I called Fish and Wildlife, and this little prick biologist came out, stuck his finger in my face and told me, ‘You’ve made a lot of money off this land. It’s time you gave back to the environment.’

“‘Well, comrade, it’s not working for me,’ I replied.

“‘I’m just doing my job,’ said he.

“‘That was a really popular response in Nuremberg,’ I told him. ‘Most of those people got stood up against the wall.’

“Now he’s the chair of the local land trust.

“I’m providing lots of public benefit here. There are lots of species and wildlife on my land that are doing really well. Why doesn’t the public owe me? As chair of the land trust, he’ll acquire land and let it sit. Within months, it will be a noxious weed patch or, if a forest, there will be deadfall, pests, brush, mistletoe. There’s no grass in the forest anymore, shade shuts it out. The forest is overstocked; we have hundred-year-old trees that are starving, dry. Which means when the forest burns, it burns hot.

“There’s a biologist under every rock out here busily protecting wildlife from the peasantry: the evil, unwashed Neanderthals.”

Sarah interjects, “We have a photo somewhere of a sign that says Fish and Wildlife Refuge. It’s surrounded by acres of knapweed. No wildlife can survive in that. It’s barren ground until it’s taken care of.”

Sarah’s favorite saddle horse was shot shortly after this incident. “Both gates were locked, so someone hiked in three miles, at night, and shot her between the eyes. They knew which horse because she was on the Web site.

“Then they banned hunting with hounds. Hounds are the only way to deal with mountain lions. Otherwise you lose one colt or calf or pet after another—I’ve lost twenty colts, found them in pieces. The biggest drop is the conception rates, a ninety-two or ninety-four percent conception rate drops to fifty percent when there’s lion around.

“Right now, if there was a lion on that deck, I couldn’t shoot it. So if a big cat is on my horse, I’m supposed to call Fish and Game. Which is a good hour’s drive from here. They issue pamphlets: Living with Cougar. Apparently you’re supposed to put your hands up in the air and look big. Are you kidding me? If there was a mountain lion or bear in Seattle, they would call out SWAT teams, the National Guard, and helicopters. I’m all for spreading the love; let’s introduce wolf and bear into the Seattle area. They’ve introduced two wolf packs into next-door Stevens County. They want grizzly next. Maybe a few grizzly wandered through here a hundred years ago, but they want them introduced anyway.

“If they treated a racial minority the way they treat and talk about people out here and me in the legislature, they’d be in trouble. But it’s all right to talk trash about the rural peasantry.”

“I’m not sure why they let us live,” says Sarah.

“So far,” replies Kretz. The room collapses in a fit of gallows humor.

From Eco-Fascists

Welcome to Absurdistan is entirely supported by readers. Please, if you’ve been here a while consider an inexpensive annual subscription.

Elizabeth Nickson was trained as a reporter at the London bureau of Time Magazine. She became European Bureau Chief of LIFE magazine in its last years of monthly publication, and during that time, acquired the rights to Nelson Mandela’s memoir before he was released from Robben Island. She went on to write for Harper’s Magazine, the Guardian, the Observer, the Independent, the Sunday Telegraph, the Sunday Times Magazine, the Telegraph, the Globe and Mail and the National Post. Her first book The Monkey Puzzle Tree was an investigation of the CIA MKULTRA mind control program and was published by Bloomsbury and Knopf Canada. Her next book, Eco-Fascists, How Radical Environmentalists Are Destroying Our Natural Heritage, was a look at how environmentalism, badly practiced, is destroying the rural economy and rural culture in the U.S. and all over the world. It was published by Adam Bellow at Harper Collins US. She is a Senior Fellow at the Frontier Center for Public Policy, fcpp.org. You can read in depth policy papers about various elements of the environmental junta here: https://independent.academia.edu/ElizabethNickson